Irregular menstrual cycles are often the first noticeable pattern in individuals later diagnosed with PCOS. Periods may be absent for months or come too frequently without a clear schedule. Ovulation may not occur regularly or at all in some cycles. This disrupts hormonal feedback mechanisms between the brain and ovaries. Some individuals mistake these patterns for stress or lifestyle factors, delaying evaluation. Hormonal tests often confirm the absence of ovulation even when physical symptoms are mild or missing.

Elevated androgen levels can cause visible skin and hair changes

PCOS is frequently linked to higher levels of androgens, hormones typically present in smaller amounts in females. These elevated levels can result in acne that resists standard treatments. Facial or body hair may grow in patterns more typical of males. This includes chin, chest, or abdominal hair growth. Hair thinning on the scalp may also appear, particularly near the crown. These features can cause emotional stress. However, some individuals experience hormonal elevation without visible signs.

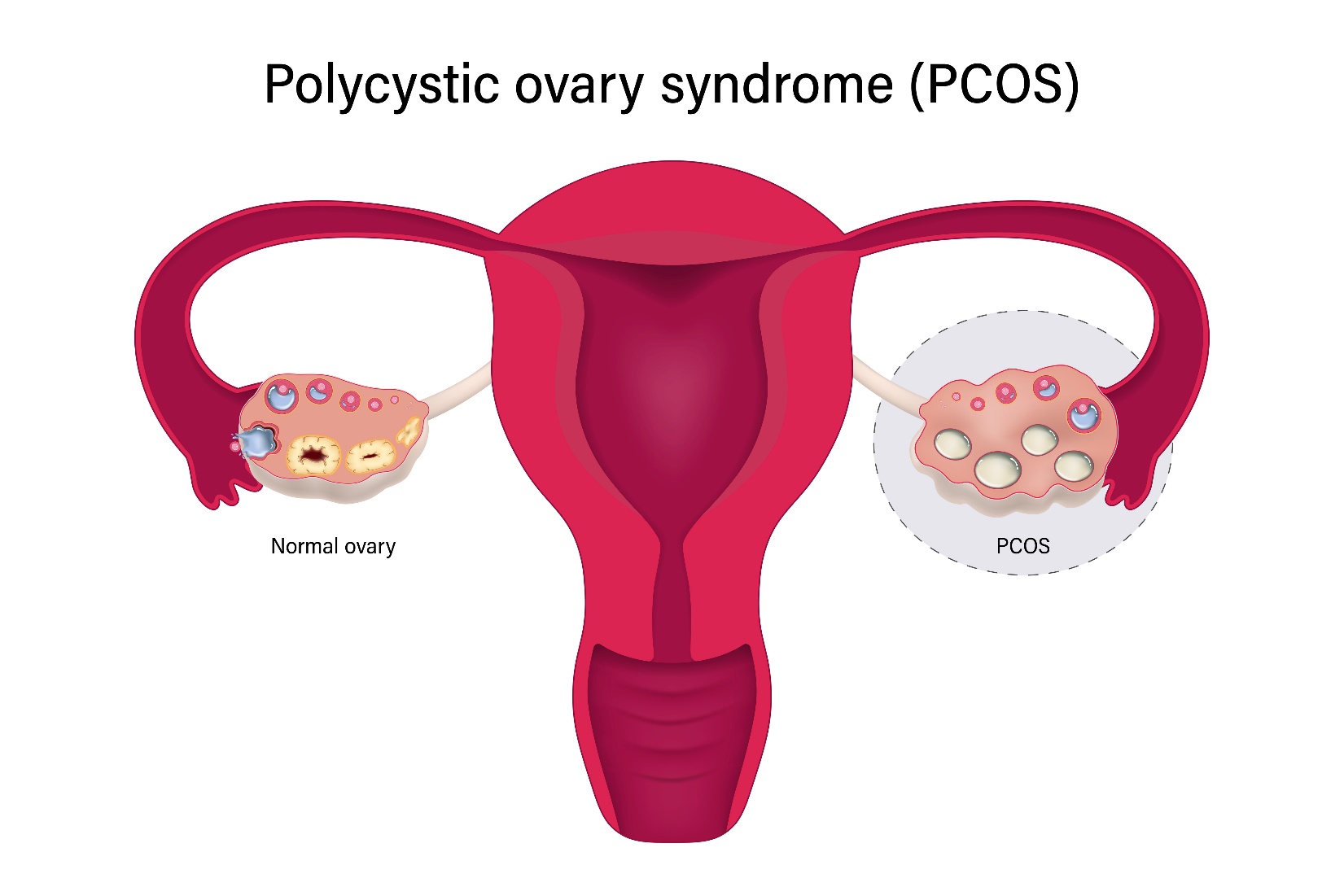

Ovaries may appear enlarged or contain multiple small follicles on imaging

Ultrasound scans sometimes reveal enlarged ovaries or multiple fluid-filled sacs called follicles. These are not cysts in the traditional sense. Each one represents a follicle that did not fully mature. Their presence supports the diagnosis but isn’t required. Some individuals with PCOS have normal-looking ovaries. Diagnosis relies on a combination of symptoms, blood work, and ultrasound—not any single feature. The term “polycystic” can be misleading for people unfamiliar with the actual criteria.

Insulin resistance plays a major role in the hormonal imbalance

Many people with PCOS have some level of insulin resistance. This means cells respond poorly to insulin signals. As a result, blood glucose remains elevated longer than normal after eating. The pancreas compensates by releasing even more insulin. Over time, this creates a hormonal environment that encourages androgen production in the ovaries. Insulin resistance may also contribute to weight gain and difficulty losing fat. Even lean individuals with PCOS can show abnormal insulin signaling.

Weight gain is common but not universal in PCOS cases

Although weight gain often accompanies PCOS, it isn’t present in every case. Lean individuals can still have hormonal imbalances, irregular ovulation, or ovarian changes. In those who do gain weight, fat tends to accumulate around the abdomen. This pattern increases the risk of metabolic complications. Weight alone is not a reliable indicator for diagnosis. Many patients with normal BMI still experience fertility challenges or skin symptoms associated with the condition.

PCOS increases the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease

People with PCOS face higher lifetime risks of developing type 2 diabetes and insulin-related complications. Persistent blood sugar elevation may lead to early pancreatic strain. Lipid abnormalities are also common. HDL may decrease while triglycerides and LDL rise. These shifts raise the likelihood of cardiovascular problems later in life. Blood pressure can trend higher than average even in younger individuals. Preventive care becomes especially important due to these overlapping metabolic concerns.

Difficulty conceiving is often what prompts a diagnosis

Many individuals first discover they have PCOS during fertility evaluations. Irregular or absent ovulation makes conception difficult. Hormonal patterns may interfere with egg release even when cycles appear monthly. Fertility treatments often begin with medications that stimulate ovulation. Some patients respond well; others require advanced approaches. Diagnosis during fertility workups reveals how long symptoms may have gone unnoticed. Even after successful pregnancy, PCOS may persist and require long-term management.

Mood swings, anxiety, and depression often accompany physical symptoms

Emotional effects of PCOS are often underrecognized. Hormonal fluctuations may contribute to mood instability and irritability. Body image concerns linked to acne or hair growth can affect self-esteem. Chronic stress around menstrual irregularity or fertility uncertainty can accumulate silently. Depression and anxiety may be higher in individuals with PCOS regardless of physical symptoms. Mental health support is sometimes overlooked but plays a crucial role in comprehensive care.

Birth control pills are frequently prescribed to regulate cycles

Hormonal contraceptives are often used to bring stability to menstrual patterns. They do not cure PCOS but help manage symptoms. By regulating hormones, these medications can reduce acne and unwanted hair growth. They also protect the uterine lining from prolonged exposure to unopposed estrogen. This lowers the risk of endometrial hyperplasia. Treatment plans vary depending on whether fertility is a current concern. Pills are one option among many.

Metformin is commonly used to improve insulin sensitivity

Metformin is a medication originally developed for type 2 diabetes. In PCOS, it improves how cells respond to insulin. This reduces circulating insulin levels and may lower androgen production as a secondary effect. Some patients report weight stabilization or improved menstrual regularity with this medication. It is often combined with lifestyle changes for better results. Gastrointestinal side effects are common initially but usually decrease over time.

Lifestyle changes can influence hormonal balance and cycle regularity

Diet, exercise, and stress management often play an important role in PCOS care. Even modest weight loss can improve ovulatory patterns in some cases. Resistance training and aerobic activity enhance insulin sensitivity. Diets focusing on whole foods, fiber, and low glycemic load may reduce symptoms. Sleep quality and cortisol regulation also affect hormonal balance. No single approach fits everyone. Consistency often matters more than intensity.

Inositol supplements are used by some patients as a non-pharmaceutical option

Myo-inositol and d-chiro-inositol are vitamin-like compounds found in food. They are involved in cellular signaling, including insulin pathways. Some PCOS patients use them to improve ovulation, cycle regularity, and insulin response. Research is ongoing, but initial results are promising. These supplements are available over the counter in many countries. They are not a replacement for medical treatment but may serve as supportive therapy in appropriate cases.

Long-term monitoring is necessary even after symptoms improve

PCOS doesn’t always require continuous treatment. But long-term monitoring is essential. Symptoms may change with age, weight, or life stage. Fertility may fluctuate, especially in the late 30s or beyond. Metabolic risks do not vanish with regular periods. Cardiovascular health and glucose regulation should still be assessed periodically. Even patients with mild symptoms should undergo routine checks. Early intervention prevents complications in later decades.